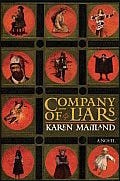

Though Company of Liars was billed as a "reinterpretation of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales," the comparison may do it a disservice. Canterbury Tales was essentially a collection of short stories in a frame that briefly, if sometimes brilliantly, describes the pilgrims who tell them. In contrast, Maitland's novel centers on the travelers themselves. The few, brief and well-told stories in Company of Liars are relevant to the central plot, which builds to a creepy, suspenseful climax.

The narrator and protagonist is a “camelot,” an itinerant seller of faked saints' relics, who prefers to travel alone. But in the sodden year of 1348, with plague breaking out in the port towns of southern England and spreading northward, a motley group of fellow travelers collects around this reluctantly kind-hearted narrator. As their journey progresses, it becomes evident that each of the nine travelers is attempting to escape not just the plague, but the truth about his or her past. But as the most mysterious of these travelers insists, the truth has a way of making itself known.

The camelot's first encounter is with the child Narigorm, who "looked about twelve years old, barefoot and clad in a grubby white woollen shift, with a bloodred band about the neck that made the whiteness of her hair shimmer." She has an odd stare. "Was that the beginning?" the narrator wonders. "Was that what caused it all—half a pastry offered to a child with eyes of ice?"

As the travelers collect and travel northward, the reader may wonder whether this is a straight historical novel or historical fantasy. The fourteenth century was steeped in superstition. As the author points out in a historical note at the end: "At that time it was considered heresy by the Church not to acknowledge the existence of vampires and werewolves." If anything, the travelers are unusually rational and skeptical for their time. Only Narigorm's weird, unchildlike skill with runestones shifts Company of Liars into the realm of spooky fantasy. (2008, 465 pages)