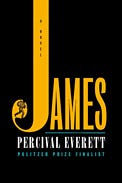

The novel James turns on two central plot elements: first, code-switching, in which a Black American speaks one way to fellow Black Americans and a different way to White Americans; second, retelling Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Huck’s fellow traveler, the slave Jim.

Code-switching is explained in the opening chapters. Jim speaks slave dialect with young Huck and with his enslaver, Miss Watson, but standard American English with his wife and daughter. In chapter 2, Jim educates a group of slave children in the slave dialect they need to use within earshot of any white person. It’s unclear where Jim picked up “correct” English, because the white characters don’t speak it. Living in Hannibal, Missouri, they use the speaking patterns typical of white rural Southerners that persisted deep into the twentieth century. Although the conceit of needing to train enslaved children in slave dialect may strain credibility, it stands in for a form of code-switching that really would have been of life-and-death importance: feigning a lack of intelligence and a contentment with servitude that few slaves must ever have truly felt.

Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, first published in 1884, was criticized for its “vulgar” language—its forthright descriptions, for example, of Huck itching and scratching. Decades later, the book became an American classic for portraying the moral struggle of a child who was taught and believes it sinful to “steal” by helping a slave escape, but who recognizes Jim as a fellow human being and a friend he feels compelled to help regardless. Huckleberry Finn was assigned in high school and college English classes for many years, but the integration of the school system meant Black students became obligated to read Twain’s frequent use of the N-word, appropriate to the setting but highly offensive. Twain wrote for his fellow White Americans, hoping to awaken their consciences, and not for Black Americans, who already understood the hell of racial prejudice only too well. In James, the word is also used, but much less frequently, and the author never violates Jim’s inner dignity.

In retelling the Huckleberry Finn adventures, James becomes a thought-provoking, suspenseful novel, all the more effective because it dispenses with elements of the earlier novel’s plot that don’t serve its own. In Huckleberry Finn, Huck and Jim are separated more than once. James naturally follows Jim rather than Huck during these periods, bringing new characters and incidents into the story and preparing the reader for later, major divergences from Twain’s story—Tom Sawyer, for example, is alluded to but never appears in James. Because I had always found the section of Huckleberry Finn when Tom reappears particularly painful to read, I didn’t mind his absence at all. (2024, Doubleday, 303 pages)