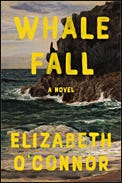

Whale Fall is set in the fall of 1939 on a fictional island off the coast of Wales. In September, the sea deposits a dead whale on its shore. The whale is a symbol, though never a heavy-handed one, of the island’s decline, seen through the eyes of eighteen-year-old Manod, who lives with her father and her younger sister, Llinos. Her mother died long ago, her best friend has married and moved to the mainland, fishermen die at sea. There are “more empty houses on the island than inhabited ones … swifts nesting in the roofs, which had buckled inwards.”

O’Connor’s descriptions vividly and unsentimentally evoke the sea, the shore, the work of fishing people, and suggest the mood and feelings of the islanders. “The pools on the tide-flats shone pale, a colour Llinos called snake-belly after we once watched a grass snake on the cliffs turn over slowly and die. Dark birds moved from one pool to the next, something wriggling in their red beaks.”

Unlike most of the islanders who speak only Welsh, Manod has enthusiastically and diligently learned English at school. So when a pair of ethnologists, Joan and Edward, arrive to collect songs, folk tales and vignettes of island life, they recruit her to translate and transcribe. Each in a different way leads Manod to dream of escaping the island without having to marry one of the few, dull young men her age who think of moving away to find factory work. Joan is naively romantic. “I love the nature here…. I love watching you all come in and out of the sea. Such a wonderful way to live…. In tune with nature.” Excerpts from the transcripts reveal lingering beliefs in the supernatural which delight the ethnologists and embarrass Manod and her father.

Whale Fall is a short novel, shorter than the page count suggests, because many of the chapters take up less than a page. It’s reflective reading, though, that doesn’t lend itself to speed. Life for Manod and her fellow islanders is hard, repetitive, slow, and laced with dangers that are taken for granted because they are ever present. The dead whale is a startling novelty, but as it slowly decays it too is taken for granted—much more so than the ethnologists who continually surprise the islanders with their innocence and disappoint with their casual heartlessness. (2024; 210 pages, including a historical note about islands that informed the writing)